Short stories and novellas are easy marks for AI-generated literature, but how will publishing cope with an influx of AI-generated books?

The first result from Dall E with the prompt “A photorealistic image of ChatGPT looking eager and ready to help a writer working on a novel.” Don’t look too closely lest it give you nightmares.

I want to start with a small protest: What is currently termed Artificial Intelligence, or AI, isn’t anything of the sort. ChatGPT is not intelligent, it’s just verbose predictive text, trained on a huge data set and capable of producing long, cogent passages. But it’s not intelligent, it’s definitely not sentient, it has no knowledge, no error detection and thus no error correction. Instead of calling it AI, I will use the term Large Language Model, or LLM, to describe ChatGPT, Bing, Sudowrite and the rest.

Now then.

Here’s the thing.

There is not a single part of the publishing industry that is ready for the onslaught of shoddy LLM content that’s heading towards it. Charles Arthur warns that the “approaching tsunami of addictive AI-created content will overwhelm us”, but I’m not sure that even that warning is stark enough. So let me try something pithier:

LLM content has the potential to destroy large swathes of the publishing industry.

Grifters will crowd out genuine writers on Kindle. LLM content will swamp submissions to literary magazines and agents. Any system based on human review will collapse, but algorithmic systems won’t do much better. It doesn’t matter how good or bad this LLM content is, what matters is how quick it is to create and thus how much of it gets produced.

This disruption is already affecting short stories and, in concert with some other self-publishing and wider macroeconomic trends, it is very rapidly going to take over Amazon’s book marketplace. Traditional publishing, especially agents, are not going to be able to escape either, though they might believe that they are safe for now. They aren’t. And authors who are focusing now on the ethical use of LLM assistance in their writing are going to find themselves in competition with people who don’t care about ethics or even readable prose. We’re at only the beginning of a massive shitshow.

Let’s start with short stories.

Clarkesworld Magazine is an online science fiction and fantasy magazine which publishes short stories, interviews and articles and has won Hugo, World Fantasy, and British Fantasy Awards. It publishes pieces between 1,000 and 22,000 words long, paying 12¢ per word or between $120 and $2,640 per submission. That makes Clarkesworld an attractive venue for authors wanting to try to make a living from their work.

It also makes it an attractive target for plagiarists and LLM scammers.

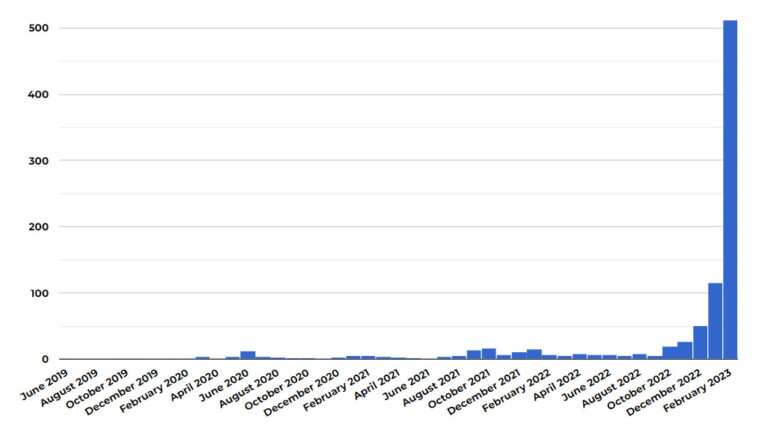

On 15 February 2023, Clarkesworld’s Neil Clarke blogged about a disturbing increase in the number of “spammy submissions” that he was seeing. Clarke wrote:

[T]he number of spam submissions resulting in bans has hit 38% this month. While rejecting and banning these submissions has been simple, it’s growing at a rate that will necessitate changes. To make matters worse, the technology is only going to get better, so detection will become more challenging.

Five days later, Clarke added a note that he’d had so many spam submissions – “over 50 before noon” – that he had to close submissions completely. There’s no reason to believe that this onslaught will stop. Clarke says that he is in touch with other editors having the same problem, but no one has a solution.

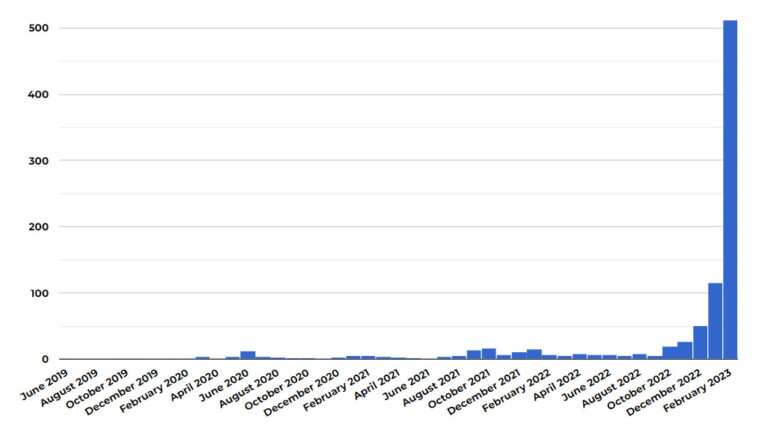

Clarkesworld submissions by month up to 20 Feb 2023.

Clarkesworld submissions by month up to 20 Feb 2023.

Let’s have a think about email for a moment, which has been dealing with spam for more than 30 years. In the early days of spam, the full burden of sorting spam from real email fell on the recipient. Now, email service providers act as intermediaries between spammer and recipient and they filter out a huge amount of the stuff before it reaches our inboxes. However, anyone with an email address will know that a lot of spam gets through and legitimate emails are often wrongly marked as spam.

There are currently no intermediaries between LLM spammers and magazine editors. The cost of LLM spam detection falls entirely and only on these editors. And, as with email spammers, there is no pressure on the LLM spammers to stop. Being blocked by a magazine doesn’t matter – you can easily create a new email and identity and have another go.

It should surprise nobody that there’s now a boom in LLM-created books on Amazon, although its true extent is impossible to measure as there’s no requirement to flag LLM content in book metadata or descriptions, and quite a big incentive not to. Reuters’ Greg Bensinger writes:

Now ChatGPT appears ready to upend the staid book industry as would-be novelists and self-help gurus looking to make a quick buck are turning to the software to help create bot-made e-books and publish them through Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing arm. Illustrated children’s books are a favorite for such first-time authors. On YouTube, TikTok and Reddit hundreds of tutorials have spring [sic] up, demonstrating how to make a book in just a few hours. Subjects include get-rich-quick schemes, dieting advice, software coding tips and recipes.

Bensinger quotes the Authors Guild’s Mary Rasenberger, who says, “This is something we really need to be worried about, these books will flood the market and a lot of authors are going to be out of work.” Yes. Yes they will.

Books with small amounts of text are an obvious target – they’re easy to generate on an LLM and it’s easier to keep on top of things like plot and consistency. A children’s picture book only has between 500 and 1000 words, whilst a chapter book for ages 5 to 7 will have around 5,000 to 10,000 words. With a little coaxing, an LLM is perfectly capable of producing this amount of text in a very short space of time. You can then use Dall E, MidJourney and other image creation engines to provide the images.

These books won’t be good – this LLM-written article on how to write a book in three days using LLMs shows just how bad a whole book of this stuff can be – but that doesn’t matter, as I’ll come on to later.

Once there’s a strategy for creating 10,000 word chapter books, it’s easy enough to extend that to 15,000 or 20,000 word novellas, at which point LLMs collide head-on with an existing trend.

That is a lot of money.

Part of the Bakewells’ success comes down to the fact that they use cheap ghostwriters and editors, so they can crank out novellas extremely quickly, and they publish in very tight niches that attract voracious readers. They know what those readers want and they can give it to them rapidly.

Indeed, this rapidity is encouraged by Amazon. There is a community of Kindle Unlimited readers who inhale books and it’s in Amazon’s interest to encourage these binge readers: They put pressure on authors to produce more, which means more choice in the Kindle store and on Kindle Unlimited, which encourage people to spend more on books and to keep their subscription going. Readers want or even expect their favourite authors to publish to a regular schedule, faster, perhaps, than it’s comfortable for those authors to write.

The Verge has published an astonishing piece by Josh Dzieza that shows just how challenging it is for authors to keep pace. Dzieza talks to indie writer Jennifer Lepp, who was struggling to meet her readers’ demands:

Lepp, who writes under the pen name Leanne Leeds in the “paranormal cozy mystery” subgenre, allots herself precisely 49 days to write and self-edit a book. This pace, she said, is just on the cusp of being unsustainably slow. She once surveyed her mailing list to ask how long readers would wait between books before abandoning her for another writer. The average was four months.

Lepp’s books are not novellas. A quick look at her back catalogue on Amazon shows that she’s writing books between 200 and 400 pages. If you assume an average of 300 words per page, that’s between 60,000 and 120,000 words. Written and edited in 49 days. That speed is completely inconceivable to me.

Lepp began to use Sudowrite, which uses OpenAI’s GPT-3 LLM and is designed specifically for fiction, and found that it made her life significantly easier. But despite the fact that her beta readers found Sutowrite’s contributions as good as, perhaps even better than, her own she came to feel disconnected from her own stories. She now uses LLM content much more judiciously.

Lepp and Bakewell’s experiences illustrate how Amazon rewards a high volume self-publishing strategy, but that the publication pace that Kindle readers want can quickly become a treadmill that human writers can’t keep up with. Your choice is either hire a bunch of ghostwriters from places like Fiverr or use an LLM to generate your prose.

Amazon itself is sending market messages that encourage LLM content creation.

She spoke with Josh Dzieza for his piece as well, (and I really do recommend you read it in full), particularly about her work with the Alliance of Independent Authors’ Orna Ross on trying to develop ethical guidelines for the use of LLMs in writing. Indeed, both Ross and Penn include “an AI statement of usage in their books to declare which tools have been used in the process of creating the finished work”.

But as valuable as these ethical guidelines are, they won’t have any impact on bad actors. Because we’re not actually talking about the Lepps, Penns and Rosses of the world. We’re not talking about people who are using LLMs as a creative tool to support their own writing process. We’re not talking about people who think about the ethics of using LLMs to write.

We’re talking about the people who don’t care about ethics and don’t care whether the stories and books they produce and publish are any good. We’re talking about commodity writers.

The high volume self-published book business is a commodity business. Authors are fungible. Books can be shorter and quality lower. They are products designed to meet the needs of readers in sometimes quite narrow niches, and it’s adherence to the tropes and expectations of those niches that is important rather than anything specific about the books. That makes the books themselves fungible as well.

This is the antithesis of what we usually think of when we think about publishing. We tend to think of authors as people who are pouring their heart out onto the page, working for years and years on their craft, on realising their vision. People for whom being read is a dream, whether that’s via a traditional publishing deal or becoming a successful indie author. These people have a story they need to tell and the act of telling it is an expression of a fundamental part of their personalities and identities. They are part of the passion economy.

High volume writers, on the other hand, are producing books quickly and cheaply – the hallmarks of a commodity.

In the short term, we’ll see more literary magazines struggling to find a way to deal with LLM spam. If there’s no easy solution, they’ll be forced to restrict their author pool in some way which, as Neil Clarke says, will damage the flow of new talent into the industry. Some magazines may even close, unable to effectively filter the wheat from the LLM chaff. These magazines are already run on a shoestring. They can’t afford to either employ more readers or pay for whatever LLM detection software arises.

We’ll see Amazon flooded with LLM-generated books and the majority of them will be shit. And Amazon won’t do a damn thing about it. There’s been an issue with plagiarism, poorly repackaged public domain books and fake reviews on Amazon for years and they simply do not give the tiniest of rat’s arses about it. I wrote about fake reviews on Amazon 11 years ago (though Forbes seems to have deleted the beginning of that article), and as far as I know, nothing substantive has changed.

And that is going to make it very, very hard for indie authors to gain traction. It’s already much harder than it used to be to break through. Indie authors have to spend a lot of money on ads to promote their books, to the point where it doesn’t seem like there’s any such thing as organic success any more. Indie authors are going to struggle to compete with LLM-assisted authors and that will drive more LLM usage.

And then it’s going to reach agents. LLM-generated novels will be submitted to agents in vast numbers, in exactly the same way as Clarkesworld was flooded with short stories, crowding out human-written books.

Novels can take years to write. My first novel took me seven years. My current work in progress might take me two. Lapp proves that you can write a novel with LLM assistance in under two months. A fully LLM-generated novel might take days. And if you can write a novel in days you can submit dozens of them to dozens of agents at once. And because a lot of agents accept submissions by email, in the truly dystopian version of this reality LLM grifters will mass-submit their LLM-generated trash to agents in the hope that just one or two will bite.

It doesn’t matter that the agents will always have the ability to spot and discard terrible books. The point is that they will be overwhelmed with LLM-generated submissions. And I am not convinced that they are ready for that. Many agents still do everything manually, which results in authors being ghosted rather than getting any kind of reply because agents are too busy to respond. How are these agents going to cope when they get swamped with LLM books?

As we’ve seen in other arenas, particularly politics and propaganda, it only takes a small number of bad actors to flood the zone with shite. Disruption is easy. Destruction is easy. Whether it’s intended or a side-effect doesn’t matter. What matters is that this problem is fiendishly hard to solve because discerning good from bad requires human cognition and we do not have actual artificial intelligence yet that can replicate human cognition.

So it doesn’t matter if the majority of authors, including LLM-assisted authors, behave ethically and thoughtfully. It doesn’t matter if LLM-assisted authors are producing good work that their readers love.

What matters is that a small number of bad actors can put so much pressure on an already fragile system that it breaks. Like Humpty Dumpty, once these systems break it will not be easy to put them back together again.

I’ll be interested to see what kind of solution Clarkesworld comes up with. We can guarantee Amazon won’t even see LLM-generated content as a problem so we can’t expect a solution from them. And it’s hard to see how agents might deal with even a small increase in submissions.

I wish I could conclude this essay with a nice solution, all tied up in a bow. But at this point, my only real solution is to hope that I’m completely wrong and that publishing won’t find itself washed away by an LLM tsunami.

But what if I’m not wrong?

What do we do then?