How Shaun of the Dead, Ted Lasso and Cabin Pressure use callbacks and repetition to create gags, move the plot forward and develop characters.

It’s been a couple of months since I’ve written about the insights I’ve gleaned from Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre by Keith Johnstone, so this week I’m taking on his rather rambling chapter on Narrative Structure which, ironically, shows very little actual narrative structure. Despite its messiness, Johnstone makes a couple of useful points, the first of which is about the importance of structure.

Johnstone suggests that one should ignore content, ie the minutiae of plot, and focus on structure instead. Story is not, he says, just a series of events, but events that are connected in a meaningful and satisfying way — in order for there to be a story, there has to be “some sort of pattern [that] has been completed”.

That leads us on to his second useful point, which is that in order to progress forwards we sometimes have to look backwards.

The improvisor has to be like a man walking backwards. He sees where he has been, but he pays no attention to the future. His story can take him anywhere, but he must still ‘balance’ it, and give it shape, by remembering incidents that have been shelved and reincorporating them. Very often an audience will applaud when earlier material is brought back into the story. […] They admire the improviser’s grasp, since he not only generates new material, but remembers and makes use of earlier events that the audience itself may have temporarily forgotten.

In comedy, you have the callback, a joke that refers back to one told earlier in the show or series. In drama, you have foreshadowing and Chekhov’s Gun, where later events refer back to earlier set-ups.

If a plot is a series of connected events that mean something, then that meaning is created, at least in part, by referring back to earlier events, dialogue or environmental cues, such as props seen in the background. Improv, in particular, sings when the improvisor calls back to an earlier line or set-up, whether their own or someone else’s. Those moments, as Johnstone identified, often get the biggest laughs because they reveal a deeper structure to the scene, one that the improvisor has created on the fly by remembering and reincorporating something said or done earlier.

Johnstone suggests that an improvisor should (his emphasis) “look back when you get stuck, instead of searching forwards. You look for things you’ve shelved, and then reinclude them.”

The same is true for writers.

I think this reincorporation can be most clearly seen in TV. A few examples I’ve been looking at recently are Shaun of the Dead, Ted Lasso and Cabin Pressure.

Shaun of the Dead

The reincorporation of Shaun’s walk to the corner shop isn’t just funny, it adds character, context and drives the plot forwards.

Shaun of the Dead is extremely well known for its use of repetition and callbacks to create not just comedy but also pathos. Whether it’s “You’ve got red on you”, “Leave him alone”, or the visual callbacks such as Shaun’s walk to the shop before/after the zombie apocalypse (above), Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright use repetition to first set up a gag, then develop character and empathy, and finally pay off with humour and/or pathos.

One of the most effective running jokes is “He’s not my dad”. Shaun first says this on page 18 to Noel, his cocky young colleague who’s asking why Shaun’s allowed to take personal calls and he isn’t. It’s a throwaway line that would go completely unnoticed if it weren’t repeated later.

On page 60, when Shaun says it childishly to his mum, Barbara, as he and Ed try to persuade them to flee to safety despite Philip, his stepdad, having been bitten, it’s a simple repetition gag.

By page 72, when Shaun reflexively says it to Ed in the car as they escape, it says something about Shaun’s character. He’s so invested in Philip not being his father that he can’t understand either who Philip is as a person or the true nature of their relationship.

But on its final outing, on page 76, after Philip has fully transformed into a zombie, it’s full of emotion and pathos. It’s only now, having lost him, that Shaun realises that Philip has done his best to be a good father.

It’s also still really funny, not just because of the repetition but because this time it has a double meaning:

ED nods to the slavering PHILIP. BARBARA looks on in shock.

BARBARA

Shaun, we can’t just leave your Dad.SHAUN

He’s not my Dad!BARBARA

Oh Shaun-SHAUN grabs a shaken BARBARA by the shoulders. BEHIND we see ZOMBIE PHILIP lunging forward into the front seat.

SHAUN

He’s not Mum. He was but he’s not anymore-BARBARA

I’m sure if we just-SHAUN

That’s not even your husband. I know it looks like him but believe me, there is nothing of the man you loved in that car now. Nothing.BEHIND we see ZOMBIE PHILIP reach forward and SWITCH THE HARD HOUSE OFF. He sits back and looks almost peaceful.

This video from Daniel Pressey summarises a lot of these examples:

Ted Lasso

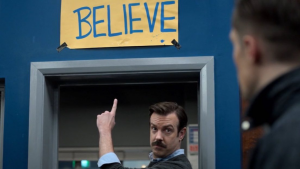

The Ted Lasso pilot, with only 31 minutes to play with, has to fire off its jokes way faster and so has less room for long-period callbacks, but writers Jason Sudeikis and Bill Lawrence still manage to get one big callback in.

The set-up is on page 9 of the script:

FLIGHT ATTENDANT (O.S.)

We’ll now be dimming the cabin…As she continues on, Beard grabs his blanket.

COACH BEARD

Better get some sleep. The jet-lag will kill us.TED LASSO

Yeah, yeh, yeh.

Then, shortly afterwards, we get what appears to be the pay-off, a false pay-off if you like, but it’s deliberately obscured by another joke:

INT. AIRPORT – EXIT AREA – THE NEXT DAY

Ted and Beard walk with their luggage toward a bunch of drivers holding signs. Ted looks a little worse for wear.COACH BEARD

You didn’t sleep at all?TED LASSO

Not a wink. No, my brain just kept cookin’. First I was thinkin’ about not sleepin’, then I was thinkin’ about thinkin’ about not sleepin’. Next thing I know they’re handin’ out warm chocolate chip cookies and the plane’s landing.COACH BEARD

I didn’t get a chocolate chip cookie. You eat mine?TED LASSO

That’s not part of the story.

But in the very final scene of the episode, we get the callback and the true payoff.

INT. TED’S APARTMENT – BEDROOM – MOMENTS LATER

Ted, finally in bed, pulls up the covers and turns off a bedside lamp. It’s COMPLETELY BLACK.TED LASSO

Shoot. Now I can’t sleep.

It doesn’t seem like much of a joke written down like this, but it really is a lovely piece of writing. After all Ted’s been through in the episode he really should be knackered, and we get this line not just as a gag, but as a way to encourage us to empathise. We all know what it’s like to be tired but unable to switch off, so in this joke, we get a laugh, some character work, and a bit of empathy. It’s masterful.

Cabin Pressure

The pilot of John Finnemore’s seminal radio comedy Cabin Pressure, similarly short, manages to give us not just a great callback joke, it makes the reinclusion core to the episode’s plot and gives us some great insights into character at the same time.

Martin, the plane’s captain, is overbearing, under-qualified and clings to his own self-importance as a way to try to make up for his acute awareness of his own considerable failings. Douglas, his second in command, is better qualified to be captain but his self-serving laissez-faire attitude to almost everything makes him unsuitable for the position. We see all of this in the short argument about whether to divert the aircraft to Bristol:

DOUGLAS

Of course, Martin, if you say we divert, then divert we shall.MARTIN

Thank you.DOUGLAS

Unless of course we were to smell smoke in the flight deck.MARTIN

What?DOUGLAS

I’m just saying, if by any remote chance, we smelt smoke in the flight deck, we would of course be duty-bound to land at the nearest available airfield with immediate priority. In this case, by a happy coincidence, Fitton.MARTIN

Yes, maybe. But I don’t smell smoke in the flight deck.Sound effect: Lighting a match.

DOUGLAS

How about now?MARTIN

What are you suggesting, Douglas?DOUGLAS

We tell the Tower we smell smoke which we do. We get to land straight away. They check the aircraft. Don’t find anything. One of the life’s little mysteries, but jolly good boys for taking no chances. Everybody is happy, and there’s jam for tea.ARTHUR

Right. That’s, you know, that’s really clever.MARTIN

No! I’m sorry, but absolutely not.

But in very final scene (again), after we’ve learnt that there’s a cat in the unheated hold that may very well die from exposure if something isn’t done, the callback no only serves a comic purpose, it’s (again), a key plot point. Furthermore, it recapitulates Martin and Douglas’s character types and relationship whilst giving us the chance to look at them from a totally different angle — Douglas’s willingness to bend the rules turns out to be what saves Martin’s arse.

MARTIN

All right, fine. Fine! All right. It’s only a job. There’ll be other jobs.

(flips on the intercom)

France control, this is Golf-Tango-India. Request immediate diversion to nearest airfield.FRANCE CONTROL

Roger, Golf-Tango-India. Do you have an emergency?MARTIN

Well, uh.

(sighs)

We’ve got…DOUGLAS

One moment, please, Tower.MARTIN

What is it, Douglas?DOUGLAS

Captain…

(lights a match)

I do believe I can smell smoke in the flight deck. Can you smell smoke in the flight deck, Captain?MARTIN

Yes… Yes, I can, Douglas. Could you request an immediate diversion, please?DOUGLAS

Certainly, Sir.

In all three cases, though more frequently in Shaun of the Dead, core parts of the narrative are created by looking back to past events, dialogue and plot points and then reincorporating them. They aren’t just a way to set up a great gag, they also provide us with a deeper insight into the characters (especially Shaun and Ted) and can form the very core of the main plot (Cabin Pressure).

So the next time you’re feeling stuck about where to take your story, look backwards. Look at the set-ups that you’ve already created and ask yourself what you can call back to. What characters have you introduced and then forgotten which you can now reactivate? How can you take a concept from the beginning and reintroduce it later on? Is there dialogue or action you can repeat in a way that’s funny or creates pathos?

Getting stuck may not mean that you need a new idea. Perhaps, instead, you need to recycle an old one; you need to find the pattern and complete it.

{ Comments on this entry are closed }