What if the majority of impostor syndrome is just a normal, sensible response to living an uncertain and precarious life in a challenging industry rife with rejection and poor communication?

Thanks to everyone who left comments or voted in the poll in my last newsletter. It was nice to hear that I’m not alone and to receive a little moral support! Writing can be a lonely business, so it’s nice to feel a bit more connection with you all.

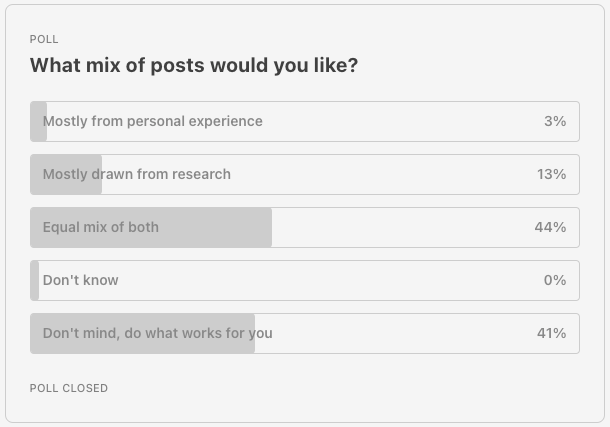

As for the poll, most people either wanted me to do what works for me, or to see a roughly equal mix of posts drawn from the research and from my own experience.

So I’m going to this week kick off with a more research-oriented post.

As it happens I have some existing areas of interest that I’ve been reading up on for another project I’m involved with: The International Collaboration on Mycorrhizal Ecological Traits, or i-COMET. If you subscribe to Word Count, you might recognise that name – we’re using the tail end of our grant to fund work on a short film, Fieldwork.

My original contribution to i-COMET was to provide a year of mentoring for early career ecologists, and collect data on their experiences to compare with a control group who didn’t have any mentoring. As part of that project, I started reading up on four attributes that we felt might affect career engagement and wanted to gather data on:

- Mentoring efficacy

- Career satisfaction

- Self-efficacy (ie self-confidence)

- Impostor syndrome

I think all of these have some relevance to writing and writer’s block, but I’m going to start with impostor syndrome because it’s something that many of us are familiar with. But before we can get deep in the weeds, (which I will do in future newsletters), we have to ask:

Does impostor syndrome really exist?

Now, why would I go and ask a question like this? We all know impostor syndrome exists, and that it particularly – but not exclusively – affects women, people of colour and other groups that are subject to prejudice. What value is there in throwing doubt on its existence? That just makes it harder for those of us fighting for equality.

That, or something rather like it, is what I thought the first time I read Stop Telling Women They Have Imposter Syndrome by Ruchika Tulshyan and Jodi-Ann Burey in the Harvard Business Review. But the more I read and re-read it, the more I had to admit that Tulshyan and Burey are right.

Much of what we think of as impostor syndrome is actually the impact of systemic barriers put up to keep us out of whatever industry, organisation, or group we’re trying to exist within. And this is as true of writing as it is of being a woman in science or technology. In fact, the publishing industry seems to have been designed to make people feel like impostors.

The first point Tulshyan and Burey make is that when women are subjected to workplace bullying, racism, and other forms of bias on a regular basis, any self-doubt, anxiety, or feeling like a fraud isn’t and shouldn’t be labelled impostor syndrome, but is instead “workplace-induced trauma”.

Writers regularly face rejection and, increasingly, ghosting when they submit their work to agents, small presses, competitions and the like. Many will say that learning to live with rejection and ghosting is just part of the job, but however you spin it, being on the receiving end of so much negativity is very likely to have an impact on our mental well-being. For many people it’s going to increase self-doubt and anxiety. That’s not impostor syndrome, that’s an impact of the wider environment we’re trying to exist in.

Tulshyan and Burey also talk about the medicalisation of impostor syndrome:

Imposter syndrome took a fairly universal feeling of discomfort, second-guessing, and mild anxiety in the workplace and pathologized it, especially for women.

[…]

The label of imposter syndrome is a heavy load to bear. “Imposter” brings a tinge of criminal fraudulence to the feeling of simply being unsure or anxious about joining a new team or learning a new skill. Add to that the medical undertone of “syndrome,” which recalls the “female hysteria” diagnoses of the nineteenth century. Although feelings of uncertainty are an expected and normal part of professional life, women who experience them are deemed to suffer from imposter syndrome.

When we take normal emotional reactions to challenging experiences – such as the uncertainty and difficulty of trying to develop or maintain a career as a writer – and pathologise them, we’re taking systemic problems and individualising them. That results in us looking inwards for solutions instead of seeking to change the actual causes of the problem, which are to be found in the way that the industry is set up.

There’s a parallel here with a strain of hypercapitalism which seeks to nationalise risk and debt and privatise profits. The publishing industry individualises risk, debt, and emotional burdens, which are all carried by writers and low-paid entry level employees, whilst profits are disbursed to execs and shareholders.

This doesn’t mean that impostor syndrome, which was conceptualised by Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Imes in 1978, doesn’t exist. What it means is that the way that we use the phrase “impostor syndrome” both in our day-to-day lives and, frankly, in academic research, needs to be re-examined and refined.

If someone has by all measures a stable professional life, if they are well-supported by their colleagues and management, if they are not having to deal with other people’s prejudice, bias or poor communication skills, if they are successful in their work, if they are praised and recognised, and yet still feel as if they are about to be ‘found out as a fraud’… Then we can talk about a syndrome of imposterhood.

For the rest of us, maybe we need to rethink things a little. Maybe we don’t suffer from an impostor syndrome which requires us to chant affirmations into the bathroom mirror every morning. Perhaps anxiety and doubt are just a normal response to the stress of being a writer, and we need to develop better coping strategies the same way we would for any other negative emotions we experience.

And perhaps we need to change the industry to remove some of these stressors.

Just a thought.

PS… As I’m currently absurdly busy with work and unable to give my lovely premium members the exclusive content I was hoping to, I’ve just gone ahead and made everything free. Which means that anyone who has taken out a paid membership is an even more generous and marvellous person now than before. Thank you for your support – it means the world to me.

Comments on this entry are closed.